NOTE: Since writing this article we've started using Behaviour Designer. It's expensive (for the asset store) but it is really good and I highly recommend it.

Do you need an economical and effective way of using behavior trees? The fluent behavior trees API allows the coder-come-game-designer to have many of the benefits of traditional behavior trees with much less development time.

For many years I've been interested in behavior trees. They are an effective method for creating AI and game-logic. Many game or AI designers from the professional industry use a behavior tree editor to create behaviors.

Indie developers (or professional developers with budget constraints!) may not be able afford to buy or build a (good) behavior tree editor. In many cases indie developers wear many hats and must stretch themselves across a number of roles. If this is your situation then you probably aren't a specialised game designer with a tools team at your disposal.

If this sounds familiar then you should consider fluent behavior trees. Your code editor becomes your behavior tree editor. You can achieve much of the power of behavior trees without having an editor or without needing specialist designers.

This article documents the technique and the open-source library. I present some theory and then practical examples. In addition I contrast against traditional behavior trees and other techniques.

Contents

Table of Contents generated with DocToc

Introduction

Behavior trees have been in our consciousness for over 10 years now. They entered the games industry around 2005 thanks to the GDC talk on AI in Halo 2. Since then they have been popularized by multiple sources including the influential AiGameDev.com.

The technique presented here is a combination of a fluent api with the power of behavior trees. This is available in an open-source library C# library. I personally have used the technique and the library for vehicle AI in a commercial driving simulator project that was built on Unity. The code, however, is general C# and is not limited to Unity. For instance you could easily use it with MonoGame. A similar library would work in C++ and other languages if anyone cares to port the code.

This article is for game developers who are looking for a cheap, yet expressive and robust method of building AI. It's cheap because you don't need to build an editor (your usual IDE will do fine) and because you don't then need to hire a game designer to use the editor. This methodology will suit indie devs who typically do a bit of everything: coding, art, design, etc.

If you are a professional game dev working for a company that has a tools or AI department, then it's possible this article won't help you. Those that can afford to build an editor and hire game designers, please do that. However fluent behavior trees could still be useful to you in other ways. For one thing they can allow you to experiment with behavior trees and test the waters before committing to building a fully data-driven behavior trees system. Fluent behavior trees can provide a cheap way of getting into behavior trees, before committing to the full-blown expensive system.

The idea for fluent behavior trees came to me during my work on promises for game development. After we discovered promises at Real Serious Games our use of them snowballed, eventually leading to a large article on the topic. We pushed promises far indeed, to the point where I realized that our promises were looking remarkably similar to behavior trees, as mentioned in the aforementioned article. This led me to think that a fluent API for behavior trees was viable and more appropriate than promises in certain situations. Of course when a developer starts using fluent APIs they naturally start to see many opportunities to make use of them and I am no exception. I know this sounds a bit like if the only tool you have is a hammer, then every problem looks like a nail, but trust me I have many other tools. And fluent behavior trees are another tool in the toolbox that can be bought out at appropriate times.

Getting the code

This C# library implements by the book behavior trees. That is to say: I did my research and implemented standard game dev behavior trees. The implementation is very simple and there is little in the way of additional embellishments. This library should work in any .Net 3.5 code-base. The reason it is .Net 3.5 is for compatibility with Unity. If needed the library can easily be upgraded to a higher version of .Net. The library has only been tested on Windows, however given how simple it is I expect it will also work on mobile platforms. If anyone has problems please log an issue on github.

The code for the library is shared via github:

https://github.com/codecapers/Fluent-Behaviour-Tree

From github you can download a zip of the code. To contribute please fork the code, make your changes and submit a pull-request.

You can build the code in Visual Studio and then move the DLL to your Unity project. Alternately you can simply put the code in a sub-directory of your Unity project.

A pre-compiled version the library is available on NuGet:

https://www.nuget.org/packages/FluentBehaviourTree/

Theory

Before getting into the practical details of using fluent behavior trees I'll cover some brief theory and provide some resources for understanding behavior trees in more depth.

If you already have a good understanding of behavior trees please skip or skim these sections.

Behavior trees

Behavior trees are a fantastic way to construct and manage modular and reusable AI and logic. In the professional industry designers will use an editor to build, tweak and debug AI. During development they build a library of reusable and plugable behaviors. Over time this makes it quicker and easier to build AI for new entities, as the process of building AI becomes gluing together various pre-made behaviors then tweaking their properties. The editor makes it easy to quickly rewire AI, thus we can iterate faster to improve gameplay more quickly.

A behavior tree represents the AI or logic that makes an entity think. The behavior tree itself is kind of stateless in that it relies on the entity or the environment for storing state. Each update re-evaluates the behavior tree against the state of the entity and the environment. Each update the behavior tree picks up from where it left off last update. It must figure out what state it is in and what it should now be doing.

Behavior trees are scalable to massive AIs. They are a tree and trees can be nested hierarchically to an infinite level. This means they can represent arbitrarily complex and deeply nested AI. They are constructed from modular components so very large trees are manageable. The size of a mind that can be built with a behavior tree is only limited by the size of the tree that can be handled by our tools and our PCs.

There is much information and tutorials online about behavior trees: how they work, how they are structured and how they compare to other forms of AI. I've just covered the basics here. Here are links some for more indepth learning:

Fluent vs traditional

Traditional behavior trees are loaded from data. They are constructed and edited with a visual editor. They are stored in the file-system or a database. In contrast fluent behavior trees are constructed in code via an API. We can say they are code-driven rather than data-driven.

Why adopt this approach?

For a start it's cheap and you still get many of the same benefits as traditional behavior trees. A usable first version of the fluent behavior tree library was constructed in a day. Contrast that to the many weeks it would take to build a functioning behavior tree editor. And you are coder a right? (I've made that assumption already). So why would you even want an editor like that when instead you can deal directly with an fluent API. You could buy an editor and there are options, especially on the Unity asset store. To buy though still costs... maybe not much, but consider that you then have to invest time to learn that particular package. Not just how to use the editor, but also how to use its API to load and run the behavior tree.

I have found that fluent APIs make for a pleasant coding experience. They fit well with intellisense, where the compiler understands what your options are and can auto-complete expressions and statements for you.

Defining behavior trees in code gives you a structured way to hack together behaviors. That's right I said hack together. Have you ever been in that situation where you designed something awesome, clean and elegant, only to find out, in the months before completion that you had to hack the hell out of it because your original design couldn't cope with the changing requirements of the game. I've learned that is very important to have an architecture that can cope with the hacking you must inevitably do at some point to make a great game. Finding a modular architectural mechanism that supports this increases our ability to work fast and adapt (we can hack when we need to) and ultimately it does improve the design of our code (because we can chop out and rewrite the hacked up modules if need be). I've heard this called designing for disposability, where we plan our system in a modular fashion with the understanding that some of those modules will end up as complete mess and we might want to throw it out. Fluent behavior trees support modular and compartmentalized behaviors, so I believe they help support the principle of disposability.

In any case, there is no single best approach to anything. You'll have to figure out the right way for your own project and situation, sometimes that will work out for you. Other times you'll find out the hard way how wrong you were. The benefit of trying fluent behavior trees is that you won't sink a lot of time into them. The time investment is minimal, but the potential return on the time is large. For that reason behavior trees can be an attractive option.

Ultimately there is nothing to stop you mixing and matching these approaches. Use the fluent API for fast prototyping while coding to test an idea. Then use a good editor when you need to build and deploy loads of

behaviors into production.

For efficient turnaround time with fluent behavior trees you need a fast build time. You might want to work in a smaller testbed rather than working in your full game. Ultimately if you have a slow build time it's going to slow you down when coding and testing changes to fluent behavior trees. If that's going to be a problem then traditional behavior trees might be more suitable for you, but probably only if you can hot-load them into a running game. So if you are buying a behavior tree editor/system you should check for that feature!

Promises vs behavior trees

It would be remiss if I didn't spend some time on promises.

In the promises article we mentioned that we had pushed promises into the realm of behavior trees. We were already using promises to manage asynchronous operations such as loading levels, assets and data from the database. Of course, this is what promises are intended for and what they excel at.

It wasn't a huge leap for us to then start using promises to manage other operations such as video and sound playback. After all these are operations that also happen asynchronously over a period of time. When they complete they generally trigger some kind of callback that we handle to sequence the next operation (eg the next video or sound). Promises worked really well for this because they are great for sequencing chains of asynchronous operations.

The epiphany came when we started seeing the entire game as interwoven chains of asynchronous operations. After all, what is a game if not a complex web of logic-chains that endure over many frames. We extended promises to support composition of game logic. During this we realized that behavior trees may have been a better fit for some of what we were doing. However it was late in that project and at the time we didn't have a library for behavior trees. So we pushed on and completed the project.

We got a lot of mileage out of promises, although it would have been better if we could have combined promises and behavior trees.

We were able to do many behavior tree-like things with promises, but there is a problem in doing that with promises that is solved by the nature of behavior trees. Behavior trees are similar to promises in that they allow you to compose or chain logic that happens (asynchronously) over many frames or iterations of the game -loop. The main difference is in how they are ticked or

updated and that behavior trees are generally more suited to the step-by-step nature of the game-loop. Behavior trees are only ticked (or moved-along step-by-step) each iteration of the game-loop. When the behavior tree is no longer being ticked, the logic of the behavior tree is stopped and does not progress. So it's incredibly easy to cancel or otherwise back-out of a running behavior tree: you simply stop updating it.

A running chain of promises isn't quite as easy to get out of as a behavior tree. They are designed to represent in-flight asynchronous operations that just happen without being ticked or updated. This means you have little ongoing control over the operation until it either completes or errors. For example downloading a file from the internet... it's going to continue until it completes or errors. Aborting a chain of promises often involves injecting another promise specifically to throw an exception in the event that we need to reject the entire chain of promises. This can be achieved by racing the abortable-promise against the promise (or promises) that might need to be aborted. If this sounds complicated and painful, that's because it is. Alarm bells should be ringing.

Since then I've used fluent behavior trees in production and have also theorized that promises and behavior trees can easily be used in combination to achieve the benefits of both. Further on I'll show examples of how that might look.

Practice

The section describes how to use the fluent behavior tree library.

Behavior tree status

Behavior tree nodes may return the following status codes:

- Success: The node has finished what it was doing and succeeded.

- Failure: The node has finished, but failed.

- Running: The node is still working on something.

Basic usage

A behavior tree is created through BehaviourTreeBuilder. The root node for the completed tree is returned when the Build function is called:

using FluentBehaviourTree;

...

IBehaviourTreeNode tree;

public void Startup()

{

var builder = new BehaviourTreeBuilder();

this.tree = builder

.Sequence("my-sequence")

.Do("action1", t =>

{

// .. do something ...

return BehaviourTreeStatus.Success;

});

.Do("action2", t =>

{

// .. do something after ...

return BehaviourTreeStatus.Success;

})

.End()

.Build();

}

To move the behavior tree forward in time it must be ticked on each iteration of the game loop:

public void Update(float deltaTime)

{

this.tree.Tick(new TimeData(deltaTime));

}

Node names

Note the names that are specified when creating nodes:

this.tree = builder

.Sequence("my-sequence") // The node is named 'my-sequence'.

... etc ...

.End()

.Build()

These names are purely for testing and debugging purposes. This allows a visualisation of the tree to be rendering to more easily see the state of our AI. Debug visualisation is very important for understanding and debugging what our games are doing.

Node types

The following types of behavior tree nodes are supported.

Action / Leaf node

Call the Do function to create an action node at the leaves of the behavior tree. The return value (Success, Failure or Running) specifies the current status of the node.

.Do("action", t =>

{

// ... do something ...

// ... query the entity, query the environment then take some action ...

// Return status code indicate if the action is

// successful, failed or ongoing.

return BehaviourTreeStatus.Success;

});

Sequence

Runs each child node in sequence. Fails for the first child node that fails. Moves to the next child when the current running child succeeds. Stays on the current child node while it returns running. Succeeds when all child nodes have succeeded.

.Sequence("my-sequence")

.Do("action1", t =>

{

// Sequential action 1.

return BehaviourTreeStatus.Success; // Run this.

});

.Do("action2", t =>

{

// Sequential action 2.

return BehaviourTreeStatus.Success; // Then run this.

})

.End()

Parallel

Runs all child nodes in parallel. Continues to run until a required number of child nodes have either failed or succeeded.

int numRequiredToFail = 2;

int numRequiredToSucceed = 2;

.Parallel("my-parallel", numRequiredToFail, numRequiredToSucceed)

.Do("action1", t =>

{

// Parallel action 1.

return BehaviourTreeStatus.Running;

});

.Do("action2", t =>

{

// Parallel action 2.

return BehaviourTreeStatus.Running;

})

.End()

Selector

Runs child nodes in sequence until it finds one that succeeds. Succeeds when it finds the first child that succeeds. For child nodes that fail it moves forward to the next child node. While a child is running it stays on that child node without moving forward.

.Selector("my-selector")

.Do("action1", t =>

{

// Action 1.

return BehaviourTreeStatus.Failure; // Fail, move onto next child.

});

.Do("action2", t =>

{

// Action 2.

return BehaviourTreeStatus.Success; // Success, stop here.

})

.Do("action3", t =>

{

// Action 3.

return BehaviourTreeStatus.Success; // Doesn't get this far.

})

.End()

Condition

The condition function is syntactic sugar for the Do function. It allows return of a boolean value that is then converted to a success or failure. It is intended to be used with Selector.

.Selector("my-selector")

// Predicate that returns *true* or *false*.

.Condition("condition", t => SomeBooleanCondition())

// Action to run if the predicate evaluates to *true*.

.Do("action", t => SomeAction())

.End()

Inverter

Inverts the success or failure of the child node. Continues running while the child node is running.

.Inverter("inverter")

// *Success* will be inverted to *failure*.

.Do("action", t => BehaviourTreeStatus.Success)

.End()

.Inverter("inverter")

// *Failure* will be inverted to *success*.

.Do("action", t => BehaviourTreeStatus.Failure)

.End()

Nesting behavior trees

Behavior trees can be nested to any depth, for example:

.Selector("parent")

.Sequence("child-1")

...

.Parallel("grand-child")

...

.End()

...

.End()

.Sequence("child-2")

...

.End()

.End()

Behavior reuse

Separately created sub-trees can be spliced into parent trees. This makes it easy to build behavior trees from reusable functions.

private IBehaviourTreeNode CreateSubTree()

{

var builder = new BehaviourTreeBuilder();

return builder

.Sequence("my-sub-tree")

.Do("action1", t =>

{

// Action 1.

return BehaviourTreeStatus.Success;

});

.Do("action2", t =>

{

// Action 2.

return BehaviourTreeStatus.Success;

});

.End()

.Build();

}

public void Startup()

{

var builder = new BehaviourTreeBuilder();

this.tree = builder

.Sequence("my-parent-sequence")

.Splice(CreateSubTree()) // Splice the child tree in.

.Splice(CreateSubTree()) // Splice again.

.End()

.Build();

}

Promises + behavior trees

Following are some theoretical examples of how to combine the power of fluent behavior trees and promises. They are integrated via the promise timer.

PromiseTimer promiseTimer = new PromiseTimer();

public void Update(float deltaTime)

{

promiseTimer.Update(deltaTime);

}

public IPromise StartActivity()

{

IBehaviourTreeNode behaviorTree = ... create your behavior tree ...

return promiseTimer.WaitUntil(t =>

behaviorTree.Update(t.elapsedTime) == BehaviourTreeStatus.Success

);

}

The StartActivity function starts an activity that is represented by a behavior tree. We use the promise timer's WaitUntil function to resolve the promise once the behavior tree has completed. This is a simple way to combine promises and behavior trees and have them work together.

This could be improved slightly with a overloaded WaitUntil that is specific for behavior trees:

public IPromise StartActivity()

{

IBehaviourTreeNode behaviorTree = ... create your behavior tree ...

return promiseTimer.WaitUntil(

behaviorTree,

BehaviourTreeStatus.Success

);

}

A real example

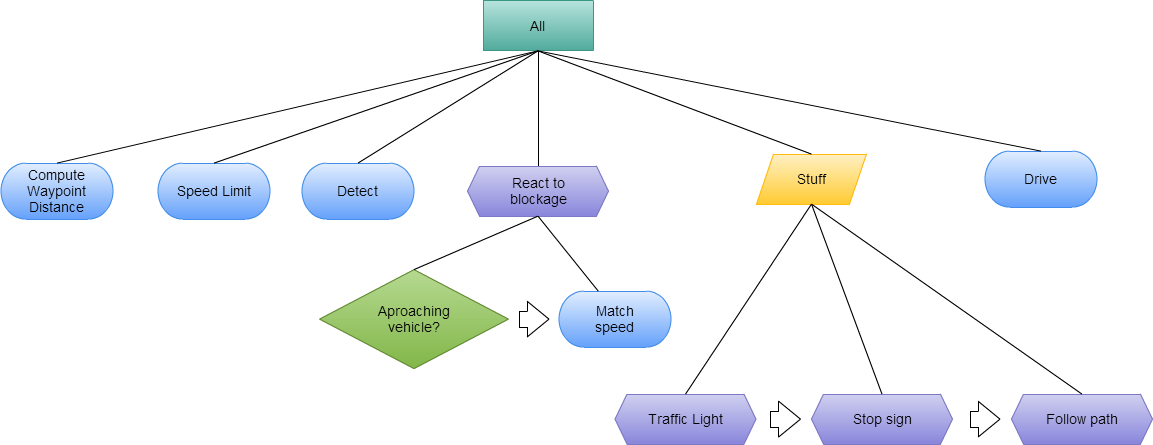

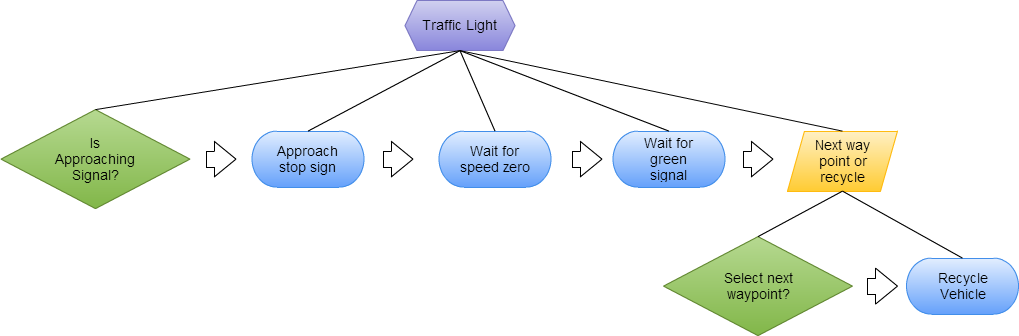

Now I want to show a real world example. The code examples here are from the the driving simulator project. This is a larger example, but in the scheme of things it is actually quite a simple use of behavior trees. The vehicle AI in the driving sim was just complex enough that structuring it as a behavior tree made it much more manageable.

The behavior tree presented here makes use of many helper functions. So much of the actual work of querying and updating the entity and the environment is delegated to the helper functions. I won't show the detail of the helper functions, this means I can show the higher level logic of the behavior tree without getting overwhelmed by the details.

This code builds the vehicle AI behavior tree:

behaviourTree = builder

.Parallel("All", 20, 20)

.Do("ComputeWaypointDist", t => ComputeWaypointDist())

// Always try to go at at the speed limit.

.Do("SpeedLimit", t => SpeedLimit())

.Sequence("Cornering")

.Condition("IsApproachingCorner",

t => IsApproachingCorner()

)

// Slow down vehicles that are approaching a corner.

.Do("Cornering", t => ApplyCornering())

.End()

// Always attempt to detect other vehicles.

.Do("Detect", t => DetectOtherVehicles())

.Sequence("React to blockage")

.Condition("Approaching Vehicle",

t => IsApproachingVehicle()

)

// Always attempt to match speed with the vehicle in front.

.Do("Match Speed", t => MatchSpeed())

.End()

.Selector("Stuff")

// Slow down for give way or stop sign.

.Sequence("Traffic Light")

.Condition("IsApproaching", t => IsApproachingSignal())

// Slow down for the stop sign.

.Do("ApproachStopSign", t => ApproachStopSign())

// Wait for complete stop.

.Do("WaitForSpeedZero", t => WhenSpeedIsZero())

// Wait at stop sign until the way is clear.

.Do("WaitForGreenSignal", t => WaitForGreenSignal())

.Selector("NextWaypoint Or Recycle")

.Condition("SelectNextWaypoint",

t => TargetNextWaypoint()

)

// If selection of waypoint fails, recycle vehicle.

.Do("Recycle", t => RecycleVehicle())

.End()

.End()

// Slow down for give way or stop sign.

.Sequence("Stop Sign")

.Condition("IsApproaching",

t => IsApproachingStopSign()

)

// Slow down for the stop sign.

.Do("ApproachStopSign", t => ApproachStopSign())

// Wait for complete stop.

.Do("WaitForSpeedZero", t => WhenSpeedIsZero())

// Wait at stop sign until the way is clear.

.Do("WaitForClearAwareness",

t => WaitForClearAwarenessZone()

)

.Selector("NextWaypoint Or Recycle")

.Condition("SelectNextWaypoint",

t => TargetNextWaypoint()

)

// If selection of waypoint fails, recycle vehicle.

.Do("Recycle", t => RecycleVehicle())

.End()

.End()

.Sequence("Follow path then recycle")

.Do("ApproachWaypoint", t => ApproachWaypoint())

.Selector("NextWaypoint Or Recycle")

.Condition("SelectNextWaypoint",

t => TargetNextWaypoint()

)

// If selection of waypoint fails, recycle vehicle.

.Do("Recycle", t => RecycleVehicle())

.End()

.End()

.End()

// Drive the vehicle based on desired speed and direction.

.Do("Drive", t => DriveVehicle())

.End()

.End()

.Build();

This diagram describes the structure of the vehicle AI behavior tree:

Here is the expanded sub-tree for the traffic light logic:

Here is the expanded sub-tree for the follow path logic:

In this example I've glossed over a lot of the details. I wanted to show (at a high-level) a real world example and using the diagrams I have illustrated the tree structure of the code.

Conclusion

In this article I've explained how to create behavior trees in code through a fluent API. I've focused on my open-source C# library with examples in this article are built on. I've used these techniques in one commercial Unity product (the driving simulator). I look forward to finding future opportunities to use fluent behavior trees and continuing to build on the ideas presented here.

If you have ideas for improves, please fork the github repo and start contributing! If you use the library and find problems please log an issue.

Have fun!